Hello and welcome back once more to Wulfhūs!

Join me as we navigate the five components of linguistics and delve a bit more in depth into what learning linguistics entails, and its importance to modern-day applications.

As is my way, I prefer to start off each post with a few questions to examine and discuss throughout.

- How do the five components of linguistics help us to study language and its structures?

- How does the development of human language differ from the communication systems of animals?

These are the two questions I will address in this post, though before we delve into the nitty-gritty content of what discussing these questions will entail, I’d like to step back and review: What is Linguistics?

<<->>

By definition, Linguistics is: the study of language and its structure. There are 5 components to take into consideration as applicable to what makes up Linguistics:

- Phonology: A branch of linguistics that deals with systems of sounds within a language or between different languages.

- Morphology: A branch of linguistics that involves the study of grammatical structure of words.

- Syntax: A branch of Linguistics focusing on a set of rules for, or as an analysis of, the word order of a language.

- Semantics: A branch of linguistics and logic concerned with the meaning of words, phrases, sentences or texts.

- Pragmatics: A branch of linguistics dealing with language in use, and the contexts in which it is used.

The five elements of linguistics, as outlined above, aide Linguists in understanding the various intricacies present with language.

The knowledge acquired from such understanding, and in such an in-depth way, provides means in which Linguists can contribute to translation activities, improve communication amoung people, and can even assist in treating speech disorders.

Let’s break it down, now, to a more in-depth outlook into each of the components that make up Linguistics.

Phonology and Phonetics

Phonology is defined as: A branch of linguistics that deals with systems of sounds within a language or between different languages.

Phonology focuses its attention on speech sounds and how the sounds of language both correlate, as well as distinguish themselves from, each other in the application of words. This “focus of attention” allows for comprehension of a given language at a deeper, denser level – by understanding the “how,” Linguists can then accurately examine the “what,” and later, the “why.”

What is the difference between Phonology and Phonetics study?

One of the key differences between these two concepts is that phonology deals more in the abstract, whereas phonetics deals more with the physical properties of sounds. An example of what this means, then, is that utterances of say – a consonant – is interminable in how it’s pronounced each time, whereas, phonologically, the sound is the same. While no two consonants sound the same when uttered, the sound uttered is represented the same.

<<->>

There are two distinct aspects of phonological study to consider. These are: Synchronic and Diachronic Phonology:

- Synchronic (Descriptive): Phonology focused on investigating sounds at a specific point of time in a language’s development – to discover sound patterns that can occur.

- E.g., (In English) “nt” and “dm” can appear within, or at the end, of a word, though not at the front of a word.

- Diachronic (Historical): Phonology focused on investigating sounds over a period of time in a language’s development – including the construction of theories – for changes and modifications encompassing this given time-period.

- E.g., “See” and “Sea”

Synchronic Phonology

The term Synchronic, as it relates to linguistics, was first coined by Swiss Linguist Ferdinand de Saussure at the beginning of the 20th century (c. 1916).

At the time “Synchronic Phonology” first came around, Saussure received much push-back. The only way Linguistics (in this context of study) was examined, was from a Diachronic perspective (more on this below). From a modern perspective, examining any “dead” language would be a Synchronic study, as the given language is no longer evolving and, essentially, “frozen in time.”

An alternative way to explain the idea of “Synchronic Phonology” would be to take a language – e.g., Old English – and analyze word order in a particular sentence from that language.

Diachronic Phonology

The term Diachronic, as it relates to linguists, was also first coined by Swiss Linguist Ferdinand De Saussure at the beginning of the 20th century (c. 1916).

Before Saussure had hypothesized both terminologies, the only “affirmed” way to examine language in this day and age was diachronically – wherein: Synchronic research within language evolution may take place, thus becoming diachronic by nature. It could not be as so, the other way around.

An alternative way to explain the idea of “Diachronic Phonology” would be to take a language – e.g, English – and analyze a given sentence’s word order; how it evolved from Old English to Middle English, and then to Modern English, respectively.

Synchronic and Diachronic Linguistics was (and is) examined hand-in-hand with each other in most instances.

Phonemes and Allophones

There are two aspects of phonology we shouldn’t neglect to mention:

- Phonemes: The smallest differing sound units in a language.

- E.g., “Cat” and “Get”: the ‘C’ and ‘G’ are both phonemes; the ‘a’ and ‘e’ are also phonemes.

- Allophones: The different way to pronounce a phoneme given its location within a word.

- E.g., “literally”: the ‘l’ is pronounced slightly different in each instance in the word, i.e., ‘li’, ‘al’, ‘ly’.

In conclusion, Phonology gives linguists the means to study “how” to “then” “why” understand language as it is.

Phonetics

As defined, phonetics is a branch of linguistics that encompasses the production and classification of the world’s speech sounds. A few of the questions that phonetics examine are as follows:

- How are speech sounds physically produced?

- How are speech sounds perceived by human cognition?

- How are speech sounds learned in second-language acquisition?

As a result, questions like these tend to cross over into other fields of scientific study in physiology, i.e. becoming “speech science.”

For the sake of this post, we’ll continue to explore other aspects of linguistics; such questions may be re-examined in a later post.

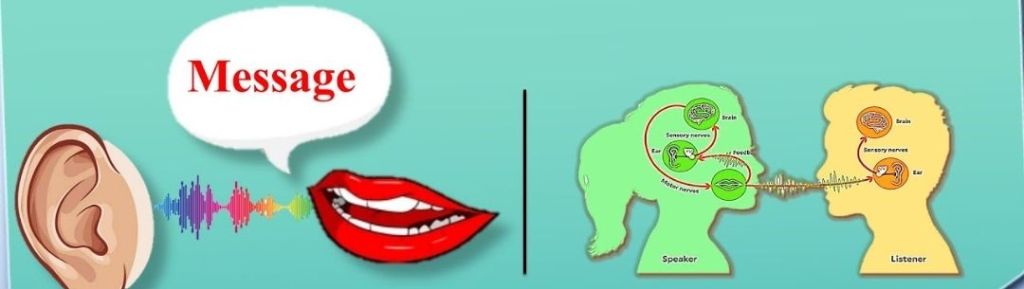

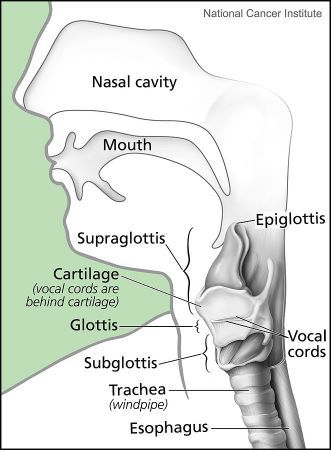

The production of speech sounds takes the use of parts of the vocal organs to produce these “sounds” that become letters within words.

See below:

To classify such diverse speech sounds, Linguists developed a guide system known as the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), first published in 1888 – the IPA has received a few revisions since its first publication.

A reputable source I’ve discovered that can be helpful in an interactive way to understand the IPA can be found here – the IPA designates a specific symbol to a given sound.

As an example, the word Phonetic would be represented as: /fəˈnɛtɪk/.

Morphology

As defined, morphology is a branch of linguistics that involves the study of internal grammatical structure of words – to include the varied formation of words within a given language’s Lexicon (complete set of meaningful units in a language – usually in the form of a dictionary).

The term “morphology” first came into use in the middle of the 19th century (c. 1859) by a German linguist, August Schleicher – one credited with some of the most profound linguistic ideas of his day and age, that being: Comparative linguistic principles (more on this in a later post).

Morphology is known for its principle of morphemes, the smallest meaningful units of grammar within a word. It is important to note, however, that morphemes are not synonymous with syllables. Syllables relate more to the pronunciation of words, which is phonological, in this sense, whereas morphemes relate more to specific structures within words, and they can host multiple syllables. More on this will be shared below.

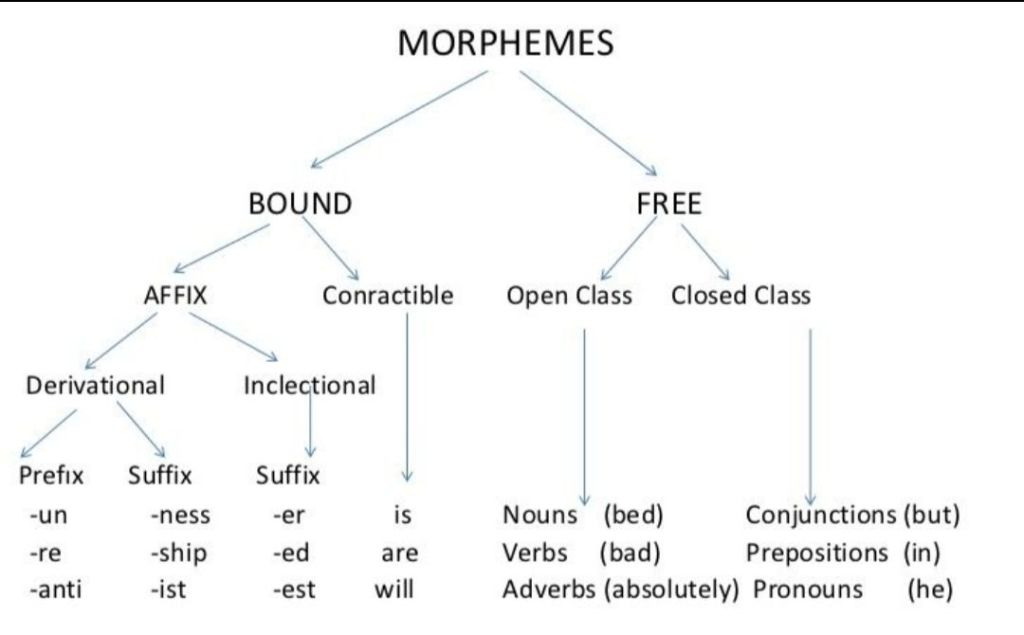

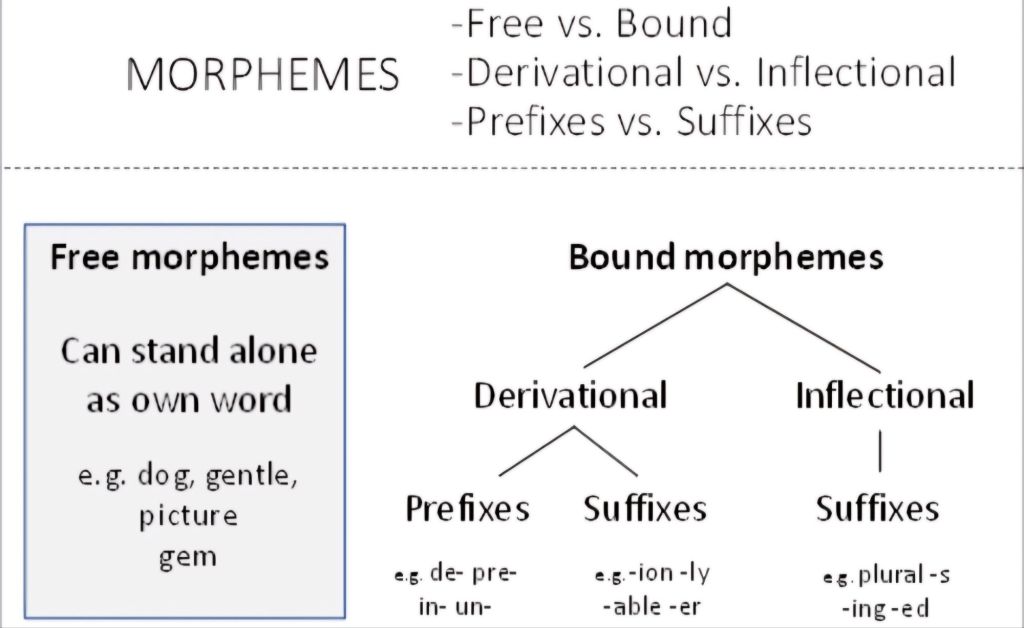

There are two main types of morphemes that have their own subdivisions. As follows:

- Free (Unbound) Morphemes: Stand-alone words

- Lexical – i.e., carry content; the “substance” of a word’s meaning as in relation to language as a whole

- Gramatical – i.e., functional, can be standalone words

- Bound Morphemes: Non-standalone, require a word integration

- Inflectional – i.e., modifies a root word without changing its grammatical category

- Derivational – i.e., modifies a root word changing its grammatical category

Please see the charts below for additional assistance with these concepts, as well as some examples:

Figure 1.0

Figure 2.0

A closing thought on morphemes as it relates to morphology:

Words can be morphemes, but not all morphemes can be words.

Syntax

As defined, Syntax is a branch of linguistics that studies the structure and formation of sentences. Syntax is a major component of grammar, and can vary between languages.

Syntax can be viewed as a standard set of rules developed to govern phrases, clauses and sentences – regardless of the syntactic order in which a language is written or spoken (more on that below). Syntax comes naturally to native speakers of a language.

Syntax is one of the major three important parts of grammar as a whole, amoung Semantics (explained below) and Phonology. Syntax allows for a speaker to correctly form complete phrases, clauses, and sentences in a logical way.

Synctactic Arrangements

There are six types of syntactic word order:

- SOV: Subject-Object-Verb

- VSO: Verb-Subject-Object

- VOS: Verb-Object-Subject

- OSV: Object-Subject-Verb

- SVO: Subject-Verb-Object

- OVS: Object-Verb-Subject

Each of these are present in languages of the world- though some of these word orders are more rare than the others. See below for a few examples:

- SOV:

- Japanese

- Korean

- VSO:

- Filipino

- Welsh

- VOS:

- Fijian

- Malagasy

- OSV:

- Tobati

- Warao

- SVO:

- English

- Spanish

- OVS:

- Hixkaryana

- Urarina

In the 1980s, a census was done by a professor of Linguistics at the University of Oregon named Russel S. Tomlin, which showed SOV Syntax was most common. SVO syntax followed suit – though presently more languages overall bear the SVO Syntax than its SOV contender.

Syntactic rules change across languages. In English, for example: conjunctions join compound sentences, adjectives modify a noun within a sentence – in a specific order; sentences often start with a subject and are followed by a verb (e.g. SVO) – that is what Syntax does for us.

Another aspect to consider when examining Syntax is diction. Diction is, in and of itself, a form of Syntax. Diction is the style of writing or speaking that someone uses; it is the choice of words. Syntax within diction also refers to the order of words within this style of writing or speaking. An example of this difference between syntax and diction, is to view it from a formal or informal perspective. An Essay or a Non-fiction book may exhibit a higher level of diction, i.e. written formally, whereas texting or speaking to friends may be much more informal and exhibit a lower level of diction.

Not all sentences are guaranteed to have meaning due to proper syntax – proper syntax can only guarantee that sentences are grammatically correct.

A closing thought on Syntax:

“Native speakers of a language learn correct syntax without realizing it.”

ThoughtCo.com

Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning in language. Semantics can be applied to single words or can also be applied to entire phrases or clauses. It is philosophical, though analytical; both practical and open to interpretation.

There are three known nations of what Semantics entails:

- Natural Meaning – an implied idea

- E.g., Steam means hot

- Conventional Meaning – a literal “answer”

- E.g., Red traffic light means stop

- Intentional Meaning – tailored for intent-based interpretation

- E.g., Debbie means trouble

“Semantics largely determines our reading comprehension, how we understand others, and even what decisions we make as a result of our interpretations.”

Study.com

One of the key takeaways of what Semantics is and entails is that theories within the field help linguists to examine complex expressions and what meaning(s) can be interpreted from such expressions. In other words, Semantics helps to highlight what an expression in a language could mean.

There are nine theories (listed below) of Semantic theories of history. I won’t go into each one in this post, but that will be a topic for a later discussion.

Those theories are:

- Ideational Semantics (c. 17th century)

- “Linguistic meaning is mental: words are used to encode and convey thoughts, or ideas…” (Britannica, accessed July 2024)

- Possible-world Semantics (c. 18th century)

- A theoretical concept of linguistic meaning to expressions as existing and interpreted by to what possibly could be or has been in the world.

- Referential Semantics (c. 19th century)

- “An apparent relation between a word and the world [and]…Linguistic expressions are signs of something other than themselves…”(Britannica, accessed July 2024)

- Fregean Semantics (c. 19th century)

- “...the meaning of an expression consists of two elements: a referent and what he called a ‘sense'” (Britannica, accessed July, 2024)

- Verificationist Semantics (c. 20th century)

- “…the meaning results from links between language and experience: some sentences have meaning because they are definable in terms of other sentences…” (Britannica, accessed July, 2024)

- Behaviourist Semantics (c. 20th century)

- “…the meaning of an expression, as uttered on a particular occasion, is either (1) the behavioral stimulus that produces the utterance, (2) the behavioral response that the utterance produces, or (3) a combination of both” (Britannica, accessed July, 2024)

- Gricean Semantics (c. 20th century)

- “…the meaning of a sentence can be understood in terms of a speaker’s intention to induce a belief in the hearer by means of the hearer’s recognition of that intention” (Britannica, accessed July 2024)

- Truth-conditional Semantics (c. 20th century)

- “…an approach to semantics of natural language that sees meaning (or at least the meaning of assertions) as being the same as, or reducible to, their truth conditions” (Wikipedia, accessed July 2024)

- Conceptual-role Semantics (c. 20th century)

- “…the meaning of an expression for a speaker is the same as its conceptual role in the speaker’s mental life” (Britannica, accessed July 2024)

Pragmatics

Pragmatics is the study of the use of natural language in communication – [of which includes] – the study of the relations between languages and their users (Britannica, accessed July 2024).

In Pragmatics, its primary focus lies upon something known as conversational implicatures – in other words, the relationship between what a speaker says, as implied, and how what is said creates inferences to its listener. What one speaker says may be interpreted as implicational of something else that another person hearing the same expression may infer.

There are seven other aspects of Pragmatics to consider, as listed below:

- Cognitive Pragmatics

- Mental processes of human communication

- Intercultural Pragmatics

- Communication between people of different cultures

- Reference-Flow Management

- Tracking syntactic references in a given expression

- Relevance Theory

- “A speaker’s every utterance conveys enough relevant information for it to be worth the addressee’s effort to process the meaning of an utterance.” (masterclass.com, accessed July 2024)

- Sociolinguistics

- Native-speaker communication between parties given a specific social group in which they belong

- Speech Acts

- “People use language and the rules of language to accomplish tasks and goals.” (masterclass.com, accessed July 2024)

- Theory of Mind

- Examines how one’s mind, or mental-state, affects what and how an expression or idea is interpreted and utilized in language.

As shown here, there are many disciplines within pragmatics and what that aspect of linguistics encompasses. Pragmatics is also a field of its own within philosophy.

Contextually, when thinking of Pragmatics within Philosophy, it refers to examining language from a more abstract, broad perspective – i.e., examining one’s linguistic ‘place’ in the world as inseparable from existence within – and, that one’s ‘utterance’ of language is shared human practice in the collective human consciousness.

More on Pragmatism as it relates to Philosophy will be examined in a later post.

<<->>

I’ve gone over quite a bit, though I have only scratched the surface of what each of the five components of Linguistics are. Let’s move on to address the last question I had raised at the beginning of this post:

- How does the development of human language differ from the communication systems of animals?

First and foremost, all animals communicate in one way or another – whether by gestures or sounds; Humans are the only ones who have developed a complex communication style and system encompassing that of language and writing.

The use of gestures, sounds, touch, smell, and other uses of the senses (e.g., Fireflies using light) are all part of a style known as a closed communication system. On the other hand, humans use a style known as an open communication system. What this means is that humans can create new meanings and messages by putting words together to form grammar in phrases, clauses, and sentences.

Studies have shown that chimpanzees (for example) could learn, and then sign, words such as banana or apple, but are still unable to learn, or sign entire phrases such as Give me an apple, I am hungry. Humans are the only ones able to learn and then sign (contextually) such phrases. The academic discipline that studies such things is called Zoosemiotics, defined as the semiotic study of the use of signs among animals. In other words, the study of the sounds and signals used in animal communication. More about Zoosemiotics will be saved for a later post.

The systems that animals use, albethey as signals, differ from human systems used – the form of symbols. The biggest case for this lies with the simple fact that animals, biologically, have more sensory receptors than humans, and instinctively react to their environment at a different level than humans.

<<->>

Conclusively, I have gone over a plethora of ideas, disciplines, thoughts, theory and basics as it encompasses Linguistics 101. There is much more that could be elaborated on, and I have only scratched the surface of what all Linguistics entails.

A few key takeaways:

- The study of language and tongue has been around since the dawn of the sciences and is incorporated into a broad spectrum of disciplines.

- Language Evolution is, in its own right, a constantly changing dynamic as new discoveries into linguistics arise, from new theories, to expounding on old ones.

- Linguistics goes beyond simply the study of language. Yes, there are five key components to what Linguistics entails, but with each of those components lies more to examine, discover, and expound upon – some aspects being sociological and psychological additionally

These are just a few things to keep in mind, possibilities in discussions are boundless, so I hope I helped to teach you something new.

Any thoughts or topics that piqued your interest in which you’d like me to examine more in a later post? Feel free to let me know in the comments below!

Until next time,

– E.K.

The Wandering Wolf

You must be logged in to post a comment.